Real Property Tax Appeals in Connecticut Guide

Co-authored: Attorney Philip C. Pires and Attorney Jason A. Buchsbaum

With fluctuations in the real estate market each year, many property owners are probably concerned about the effect that their property values may have on their local real estate taxes. A property owner is also likely to be interested in a potential remedy if his or her property is overassessed. In Connecticut, real property taxes are determined at the local municipal level and are based on home values as of a certain date. Connecticut municipalities are required by statute to revalue property for purposes of taxation every five years in an attempt to keep the tax burden uniform and fair and account for market fluctuations. Connecticut statutes require that every property be assessed at 70% of its fair market value as of the revaluation date.

Before determining whether a particular property is overassessed, a property owner must first determine the date of revaluation. The revaluation date is always set as of October 1st of the revaluation year. For instance, if a local municipality conducts a revaluation on October 1, 2025, the value of a property in that municipality is set as of October 1, 2025 for the succeeding five years regardless of market conditions during that five year time frame.

Once a property owner determines the revaluation date for the property in issue, there are two potential statutory remedies available to a property owner if he or she wants to challenge the assessment of the property as of that date. Each remedy is discussed below.

Statutory Remedy 1 - Real Property Tax Appeals under Conn. Gen. Stat. § 12-117a

Any taxpayer claiming to be aggrieved by the assessment must first bring an appeal to the Board of Assessment Appeals (the “Board”) in the municipality where the property is located. This appeal is made by submitting a form to the Assessor that can be obtained from the Assessor’s office in the municipality, and the property owner can submit with the appeal form whatever documents or other evidence that they feel would be useful in determining value. The Board will then schedule a hearing with respect to the appeal. The Board is an administrative body composed of citizens of the municipality. The members of the Board listen to the taxpayer’s complaints and arguments about the assessment of the property, and they have the authority to decrease – or increase – the assessment if they find justification for doing so. Hearings before the Board are informal, there is no judge or jury, and there are no rules of evidence. In fact, in some towns, the appeal will be heard by a single member of the Board who will then confer with the full Board at a later date to reach a determination concerning the appeal. A taxpayer may appear alone, with or without counsel, and with or without a real estate appraiser. The Board hears appeals for all types of property within the municipality, from simple, single-family residential properties, to complex commercial and industrial properties. Also, if the Board increases or decreases an assessment, the new assessment set by the Board generally remains fixed until the next revaluation.

If a taxpayer wishes to challenge his or her property assessment in a revaluation year, it is especially important to appear before the Board in the initial year of the revaluation. Though a taxpayer may appeal to the Board in any given year, appealing an assessment in a revaluation year allows the taxpayer to challenge all five years in the revaluation cycle, and therefore, it allows the taxpayer to maximize the potential tax savings.

The Board will issue a written notice to the taxpayer indicating whether the property value will be increased, decreased, or remain the same. If the taxpayer is dissatisfied with the Board’s decision, the taxpayer may appeal that decision to the Connecticut Superior Court. Appeals to the Connecticut Superior Court must be taken within two months of the date the Board mails notice of its decision to the taxpayer. The date notice is mailed should be indicated on the notice itself.

Taxpayers should make the best presentation possible to the Board, with the hope of obtaining a favorable decision and avoiding the time and expense of an appeal to Superior Court. Additionally, some tax appeals simply do not involve enough money to justify a trip to Superior Court, which makes the quality of the presentation to the Board even more important.

Issues in a real property tax appeal to the Connecticut Superior Court under Conn. Gen. Stat. §12-117a generally involve value determination and overassessment. In these types of appeals, the taxpayer simply asserts that the property is not worth as much as the assessor has valued it. Like most civil lawsuits, tax appeals are typically settled before trial. If the taxpayer and the municipality cannot reach a settlement, then the Connecticut Superior Court holds a trial to determine the value of the property. The trial judge will hear the appeal de novo – without any regard to the evidence presented to the Board or the decision reached by the Board. It is the property owner’s burden to prove that the value of the property is less than what the town has set it at, and this is usually done with the testimony of an expert real estate appraiser. Trials in tax appeals are generally a battle of expert witnesses – real estate appraisers – who testify about value of the property and the methodology they used to derive that value.

Once a tax appeal to the Connecticut Superior Court is resolved, by either settlement or trial, the new value generally remains fixed until the municipality’s next revaluation, with limited exceptions, such as new construction or demolition. A taxpayer is generally prohibited from appealing assessments in subsequent years during the same revaluation period after obtaining a judgment in the Connecticut Superior Court.

Statutory Remedy 2 - Real Property Tax Appeals under Conn. Gen. Stat. § 12-119

A second statute, Conn. Gen. Stat. § 12-119, actually allows a taxpayer to appeal directly to the superior court without first appearing before the Board, but for very limited reasons. An appeal under Conn. Gen. Stat. §12-119 must be taken within 1 year of the valuation date. Therefore, to challenge a value as of October 1, 2025, the appeal must be taken no later than October 1, 2026, regardless of when the taxpayer initially receives notice of the assessment. 12-119 appeals are held to a much stricter standard, and they are not a substitute for appearing before the Board. Whereas in a 12-117a tax appeal, the taxpayer must show that the property was overassessed, in a 12-119 tax appeal, the taxpayer must show that the assessment was manifestly excessive and that it resulted from an illegal act of the assessor – that the assessor disregarded the valuation statutes when it determined the assessment of the property or that the taxpayer’s property is nontaxable. The taxpayer bringing a 12-119 appeal faces a very onerous burden to prevail and is seldom successful.

Conclusion

Although Connecticut’s statutory real property tax appeal scheme was intended to simplify the appeal process and to provide a relatively inexpensive method of appeal, it is complicated if meaningful results are expected, and it has procedural and other traps for the unwary property owner. We therefore recommend that you obtain the services of a competent Connecticut tax appeal attorney to represent you at every stage of the process to maximize the potential tax savings of the appeal. Our firm handles tax appeals throughout Connecticut. Please contact us here.

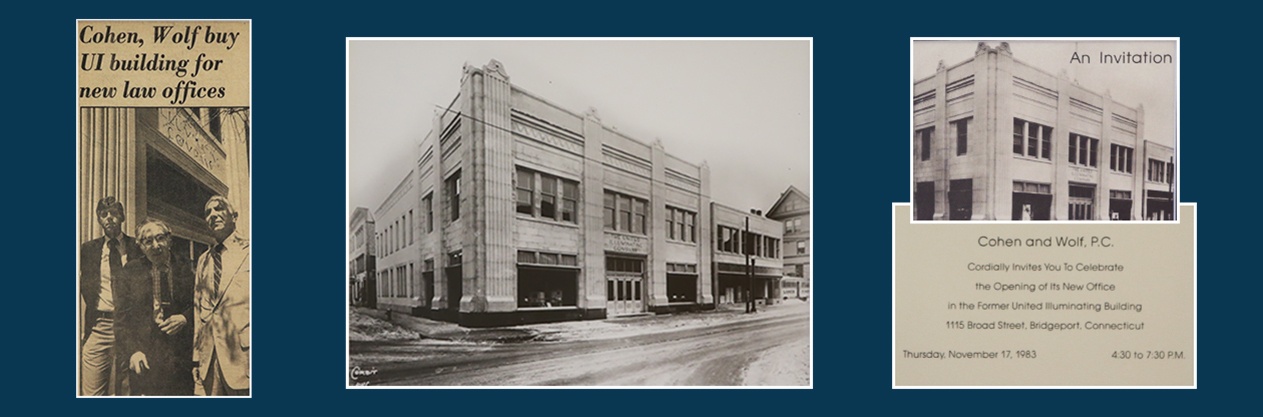

Philip C. Pires and Jason A. Buchsbaum are members of the Municipal Law and Litigation Groups at Cohen and Wolf, P.C. Philip Pires and Jason Buchsbaum regularly represent municipal, corporate, and individual clients in all aspects of commercial and municipal litigation, including municipal property tax litigation.

Practice Areas

Attorneys

- Principal

- Principal